The stories of boats and their owners are commonly intertwined – Eric Tabarly and Pen Duick, Sir Francis Chichester with Gypsy Moth, Blondie Haslar and Jester – but with boats now outliving their owners by as much as a century, it’s equally common for these stories to become divorced.

And what is it that directs the whims of the public consciousness? At one time she raced shoulder to shoulder with Olin Stephens’ Dorade and her owner was a notable US adventurer, but who today remembers Highland Light and Dudley Wolfe?

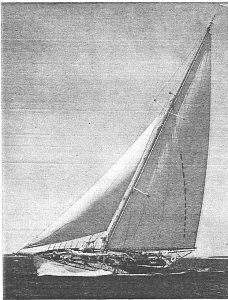

The Yacht – Highland Light

LOA: 61ft 8in Cutter rig

LWL: 50ft 0in Built: 1931

Beam: 15ft 4in Builder: Geo. F. Lawley, Mass.

Draught: 9ft 3in Designed: Paine, Belknap & Skene

Sail Area: 2324 sqft

Having been launched within a year of Dorade and just prior to the start of the 1931 Transatlantic Race, the two white yachts would have been pristine and filled with the excitement of unknown potential as they met on the start line at Brenton Reef off Newport, RI. From there, Dorade, smaller at just 52ft LOA, took a bold course far to the north and entered the history books as one of the greatest ocean racers ever built, while Highland Light raced nobly and successfully for many years, but to far less enduring acclaim.

Indeed, as they sighted the Lizard at the end of that race, dicing alongside the 71ft Herreshoff ketch Landfall, those aboard the big cutter Highland Light believed that they were fighting for line honours. Only to be informed by a passing smack that Dorade – in demolishing a record of 60 years standing – had already been in for two days.

The battles continued later that year with the running of the Fastnet Race – which was to become one of the Fastnet epics – as Highland Light, with Dudley Wolfe at the helm, this time alongside the Charles Nicholson-designed Patience lost out for line honours by just 78 seconds after a tooth-and-nail battle around the entire 600-mile course. But Dorade, just an hour and a half behind on the water, thrashed all on corrected time.

Returning home in 1932 Highland Light completed her most famous triumph, becoming the first yacht to complete the Bermuda Race in less than 3 days (25 minutes less, in fact, averaging 8.8 knots) under charter to her designer, Frank C Paine, who reputedly always had a soft spot for her. Wolfe had been away skiing in Europe during the record-breaking voyage and it must have irked him that such great acclaim was achieved without him onboard. For the next few years Highland Light with Dudley Wolfe at the helm became fixtures on the US ocean-racing circuit, until Wolfe undertook an ill-fated trip to K2 in the Himalayas in 1939.

With her famous owner deceased, a future of hard graft faced the once glamorous yacht – though she was perhaps no less loved through this phase. Following her bequest to the Annapolis Naval College, Highland Light was raced and sailed heavily, including entry to every Bermuda Race until 1958, generally performing well in her class and becoming beloved by many a Navy-man that passed through the college. Among these sometimes fledgling sailors and voyagers were future Apollo astronauts, Jim Lovell and Wally Schirra as well as Admiral Halsey, while some recount that every US President between 1933 and 1953 had been entertained aboard.

It seems that many who learned their navigation and seamanship skills aboard – just as Wolfe intended with his bequest – retained a soft spot for Highland Light, long after leaving the college. One of those was a guy called Bill Sherar, who remembered Highland Light fondly from his time sailing her at naval college when as, bowman of Bolero, he helped finally break Highland Light’s Bermuda Race record 24 years later.

Ejection from the Navy came when she was designated as surplus in 1965, and following this Highland Light has been through some rough times. She was laid up in Norfolk, Virginia for a while after suffering damage during a tow, and a rebuild was halted when she and all her gear were stolen from her then owner, who only won back ownership following a lengthy court battle.

With such a renowned builder – only the year before her launch, Lawleys had produced the America’s Cup contenders, Whirlwind and Yankee– not to mention the pedigree of her designer, coupled to a fine racing and Naval history – all documentation from her time in the US navy is lodged in the Admiral Nimitz library under her title, USS Highland Light, IX-48 – you would have thought that her future was secure, but hard times can quickly overtake a wooden yacht and Highland Light is now in need of a friend.

Highland Light is currently for sale with plans and much of her historic documentation as a rebuild project.

The owner – Dudley Francis Cecil Wolfe (1896-1939)

Born in New York State in 1896 and wealthy heir to a large fortune, Dudley Wolfe was not content to adopt the idle life of a US playboy and he abandoned his schooling early in a whirlwind attempt to see service at the end of the Great War in Europe. Initially rejected by the Maine National Guard and other US military units for having poor eyesight and flat feet, he continued to follow his conscience by enlisting, first with the American Ambulance Service in France and later as an ambulance driver with the Italian Ambulance Service, by whom he was twice decorated. Late in 1918 he enlisted with the French Foreign Legion with whom he was to remain until the signing of the armistice.

Following his repatriation to the US, Dudley Wolfe resumed his schooling, entering Harvard to play football (American), and through the 1920s he augmented his reputation as an adventurer possessing a string of racing yachts, including the schooner Mohawk, commissioned for the 1928 race to Spain. Mohawk proved unsuccessful and so Wolfe had America’s Cup designer, Frank C Paine, of Boston, draw Highland Light for him.

Aboard Highland Light, Wolfe carved out a reputation as a determined off-shore yacht racer on both sides of the Atlantic, and he was still only in middle-aged when, in 1939, he became the first man to die on what was to become the world’s deadliest mountain, K2.

In what was only the fourth ever attempt to climb the world’s second highest peak, Dudley was left to die when his fellow climbers turned back just a few hundred metres below the summit – the mountain, on the border of Pakistan and China, would not finally be conquered until 1954. When news of his death, and of three other climbers who died trying to return to him, reached the outside world a scandal followed in the US and Britain, as, with zero experience of high-altitude climbing, Dudley had no real business being on the mountain at all. Many believed that he had been persuaded to join the project simply because he had the money to fund the attempt and was then left to die alone in a tent at 7,000 metres. To others, though, it was the case that he talked – or bought – his way onto the team as a way of proving his manliness to his recently ex-wife. Whatever is the truth, it was a sad and early end.

In the will opened upon his death, it was discovered that Dudley Wolfe had bequeathed $100,000 of his fortune and his beloved racing yacht, Highland Light, to the Naval Academy of Annapolis, to be used there in the training of students in the principles of seamanship and navigation. She remained there, in that role until 1965.

Dudley Wolfe’s frozen body was eventually discovered on the slopes of K2 in 2002.