When Charles Sibbick’s body was found at the mouth of the Medina River on the Isle of Wight in February of 1912, it marked the sad and mysterious end of possibly the most forward-thinking yacht designer of his time. But what is perhaps even more tragic than his untimely end is that his reputation for building advanced, beautiful, lightweight racing machines that were the best in the world has been allowed to dip below the waves of history.

We like to think of light displacement hulls, bulb keels and miniscule wetted area as modern concepts, unsuited to wooden boat building techniques. And it’s comfortable to believe that these ideas have been developed in the electronic eddies of computer memory, while being spawned through the technological alchemy of blending carbon fibre, high-strength epoxies and other exotic materials. But, not a bit of it.

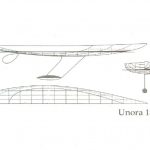

It was only changes in the racing rules, leading to the introduction of the International, or Metre Rule in 1907, that brought an end to a strand of development in plank-on-frame boat building that was utilising all these features. A look at the lines plans of one of Charles Sibbick’s small racing craft is of interest to many a modern armchair hydrodynamicist, and to spot a date of perhaps 1895 is truly staggering! One can only imagine what Sibbick might have done if he had access to carbon-fibre?

Through this time, Sibbick’s Albert Yard on the Medina River, Isle of Wight was a global hub for building boats of this type – known as raters, the largest being around the size of a 12-Metre – and his designs and delicate yachts were being delivered to all parts of the planet. Orders for yachts and drawings were being quickly fulfilled and rapidly dispatched to yachting centres across Europe, North and South America, Russia, Skandinavia, even Asia and Australia. The haste was necessary as the performance of these craft could be superceded, often by Sibbick himself, within a matter of months. And the minute scantlings combined with extreme shapes and minimum volumes meant that once the boats weren’t winning, like Fomula One cars today, they had little other practical use: they were absolutely useless for any kind of cruising.

Not all Sibbick’s output through this time were light-weight racing machines, but these raters, built quickly to a high standard from quality materials, formed the core of his business. Being light and nimble, while costing perhaps £300 for a 2 1/2 rater, these yachts allowed amateurs access to competitive sailing, but they were also popular among the era’s rich and famous including both yachting and everyday nobility. Perhaps the greatest challenge for Charles Sibbick came in 1896 with a commission to build a 1-Rater for no less than Prince George himself, later to become King George V.

Dealing with nobility would not have been an issue for Sibbick – his customer list included other of the world’s ruling families. What might have been a problem, though, was that the Prince was desperate to fill a little time between Naval duties and required the yacht to be built within just one week. It perhaps says much of the character of a boat builder of whom little firm personal history remains that amid the melee of his usual orders he took up the challenge – instigating 24-hour shifts and acetylene lighting at the yard. White Rose hit the water six days later, going on to win first prize at the Castle Yacht Club regatta two days after that.

The raters that Sibbick produced were the best at what they were designed for, but the constant drive for performance, as it does today, produced flaws in other areas – though performance, and build-quality were prerequisites, these raters were inherently unseaworthy beyond racing conditions. And these rapidly-built, yet rapidly redundant, extreme yachts were drawing notice at the time for the blind alley down which they were pushing yachting.

Attempts to reverse the trend with amendments to the rating rule had been ongoing throughout Sibbick’s career, and this eventually led to the international adoption of the Metre Rule in 1907, which also overcame the problems of handicap among yachts racing from different nations. The heavier scantlings and greater volumes of the Metre Rule may have incurred greater initial build costs, but with even the elite racing classes expected to have reasonable lifespans and improved seaworthiness, the yachts could percolate down the yachting hierarchy with time, as well as performing as cruisers. We should be grateful, as the highly successful Metre Rule, which remained in common used until well into the latter half of the twentieth century, has meant that we still have some legendary yachts to play with today.

Though Sibbick was among the best at what he did, he must have recognised where his and the designs of the other leading racing designers of the time were taking the yachting world. And as one of the foremost designers and builders of his time, his views were sought and assimilated into the rule that eventually superceded his best designs.

By the time the Metre rule was introduced, Sibbick’s business had already closed. He had tried to alter the focus of the yard with the changing rules, but the public seemed unwilling to accept his heavier-built designs with the same relish as before. Which is somewhat inexplicable if you look at the elegant and seaworthy Saunterer or the 16-ton Thames Measurement yawl, Thalassa, both of which are from his later period and still sailing today. It’s possible the reason for his business’ demise is that, as a craftsman, he had always put more work into his vessels than he was able to charge for – it’s the recurring issue for many a boat-builder down the years as well as today. If this was the case, building larger, more labour-intensive yachts might only have exacerbated the issue, but that’s a guess. Whatever the truth, in 1903 his creditors – mainly the yard’s suppliers – caused Sibbick’s company to cease trading, though the Albert Yard continued without him.

Popular lore has it that when his body was found floating down the Medina at the age of 62, it was the result of suicide brought on by the demise of his business, but, though little is certain at this distance of time, the taking of his own life is unlikely. His death occurred nine years after his business wound up and his family had a long-established property building business based on the Isle of Wight. If nothing else, Sibbick would have had ample work in this trade, in which he’d been successful before building yachts, and, even so, there are plenty of boats recorded as drawn and even built by Sibbick in the years after his boat building business closed.

The most likely reason for his untimely end is probably the most obvious one: that his death was the result of an accident while out in his dinghy early one morning. His body was found some days after the discovery of his empty dinghy and perhaps this interlude was the cue for unsavoury rumours to begin to percolate.

Whatever the truth of Sibbick‘s death, his once enormous reputation dissipated and his name has slipped well below that of his contemporary competitors such as Fife, Nicholson and Payne in the hierarchy of modern classic yacht-chat. But he was no less a designer and builder for that.

Perhaps it was the unusually global nature of his business that played a part in quickly fragmenting Sibbick’s legacy, or perhaps it was the relatively short though prolific career – he designed and built more than 300 boats in a career that rose and fell in just 24 years. However, the good news is that with today’s clamour for all things classic and yachty, things are beginning to turn around.

The number of known, existing Sibbick yachts stands at around 20, but that number is slowly growing and interest is being swelled by a number of means. An appreciation hub exists on Facebook, which is gathering information about the man, while a new half-rater, Diamond, was built to Sibbick’s plans in strip-plank, being launched in 2011 and is now for sale.

To some it may seem fitting that the Sibbick reputation has been as little resilient to the ravages of time as his boats and his business proved to be, but it also may be that his world-wide success has meant that what of his output still exists is scattered to the four winds – any number of unrecognized Sibbicks may be laid up or in use today around the globe. Whatever the arguments, though, a look at the 15-ton ocean racer, Thalassa; the Godinet Rater based in Italy, Bona Fide; Cpt Oates’ Saunterer or the lines of any of Sibbick’s rapid raters only seeks to deepen the mystery surrounding the decline in the name of one of the greatest yacht designers and builders ever to have graced our world.